A recent study examined the link between eating patterns and mental health among night shift workers. Previous research has shown that individuals working night shifts are at a heightened risk of experiencing mental health challenges, such as increased symptoms of depression and anxiety.

The study focused on individuals undergoing simulated night shift work, comparing those who ate both during the day and at night with those who exclusively ate during daylight hours. The findings revealed that those who maintained daytime-only eating habits were seemingly protected from worsening mood symptoms, while those who ate at night in addition to the daytime experienced an increase in symptoms of depression and anxiety.

This discovery offers a potential avenue for enhancing the mental well-being of the numerous Americans engaged in evening, rotating, or on-call shifts. Nevertheless, further research conducted beyond controlled sleep laboratory settings is necessary to validate these findings.

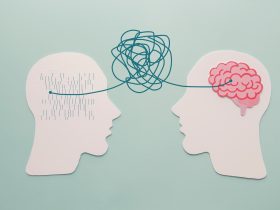

Night shift work disrupts the alignment between the body’s circadian rhythm, the internal 24-hour “clock,” and the sleep/wake cycle, potentially raising the risk of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, studies consistently demonstrate that night shift workers face an elevated risk of mental health issues, including heightened depression and anxiety symptoms.

Frank A. J. L. Scheer, PhD, the director of the Medical Chronobiology Program at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and one of the study authors, stated, “Our findings provide evidence for the timing of food intake as a novel strategy to potentially minimize mood vulnerability in individuals experiencing circadian misalignment, such as people engaged in shift work, experiencing jet lag, or suffering from circadian rhythm disorders.”

These findings were published on September 12 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The Rise in Depressive and Anxious Symptoms

The study enrolled 19 participants, comprising 12 men and seven women, who were subjected to simulated night shift conditions within a laboratory setting. This simulation induced a circadian misalignment, meaning their internal biological “clock” was out of sync with their behavioral and environmental rhythms, including their sleep patterns and exposure to light and darkness.

The participants were randomly divided into two meal-timing groups. One group followed a schedule of eating during both day and night, which is common among night shift workers. The other group exclusively consumed meals during the daytime.

Researchers regularly evaluated the participants’ mood levels resembling depression and anxiety throughout their waking hours. These mood states mirrored those typically observed in individuals with depressive or anxiety-related disorders.

During the simulated night shift, individuals who ate meals both during the day and night experienced a 26% increase in mood levels resembling depression and a 16% increase in mood levels resembling anxiety, relative to their initial levels.

The impact on mood was more pronounced among individuals with a greater degree of circadian misalignment.

Conversely, individuals who confined their meals to the daytime witnessed no significant alterations in their mood levels resembling depression or anxiety.

Optimizing Meal Timing for Enhanced Mental Health

Dr. Christopher Palmer, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, who was not involved in the recent study, expressed his intrigue regarding this research, which aligns with existing knowledge about the health risks associated with night-shift work.

“We have long been aware that shift workers exhibit elevated rates of mental disorders, notably depression and anxiety disorders, as well as metabolic conditions like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease,” he noted.

While Dr. Palmer emphasized the need for further investigation, he suggested that, based on this study and similar findings, it may be prudent for shift workers to experiment with consuming their meals during daylight hours for a few weeks. This trial could help determine if there is a discernible impact on their mood and anxiety symptoms.

Though this study primarily pertains to shift workers and those with disrupted sleep patterns, research indicates that late-night eating could also affect the health of individuals who do not work at night.

Studies have uncovered a connection between late-night eating and an increased risk of coronary heart disease, challenges in weight management, and overconsumption.

Furthermore, individuals who frequently indulge in midnight snacks, a phenomenon known as night eating syndrome, may face a heightened risk of depression and psychological distress.

Dr. Palmer, the author of the upcoming book “Brain Energy: A Revolutionary Breakthrough in Understanding Mental Health—and Improving Treatment for Anxiety, Depression, OCD, PTSD, and More,” acknowledged the complexity of such research, given the numerous factors at play, including alterations in sleep patterns, circadian rhythms, eating habits, stress responses, and mood symptoms.

“Disentangling these factors has proven challenging,” he remarked. Therefore, the present study holds significance in the field as it isolates one specific variable—the timing of meals.

Another potential drawback of late-night snacking is the tendency to choose calorie-laden, sugar-laden, and sodium-laden junk foods over healthier alternatives.

Dr. Palmer advised, “If individuals recognize this pattern in their own lives, they might consider adjusting their bedtime earlier. Many Americans are already grappling with insufficient sleep, so prioritizing sleep can be a step toward breaking this cycle.”

Find Us on Socials