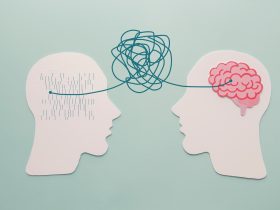

While many Americans understand that their online posts are subject to public exposure, it may come as a surprise that their health and mental health data is being sold based on their digital activities.

In an increasingly connected world, it has become nearly impossible to maintain complete online privacy, and as a result, your personal information is readily available.

A study conducted by Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy has revealed that data marketers are selling the personal information, including names, addresses, medications, and conditions, of individuals diagnosed with mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, or bipolar disorder.

John Gilmore, head of research at DeleteMe, explained, “Marketers and individuals in the data broker industry gather data from third parties and identify potential buyers to whom they can sell it. Personal health information has always been a highly valuable commodity.”

For instance, the Duke study found that third-party apps designed to assist individuals in managing their mental health conditions often sell this sensitive information to data brokers.

In their investigation, researchers established connections with data brokers and identified 11 companies selling health-related data, including details about antidepressant use and various conditions such as anxiety, insomnia, Alzheimer’s disease, and bladder-control issues.

While some of the data was generalized, like “a certain number of people in a particular zip code have depression,” other information included personal details such as names, addresses, and income levels of individuals with specific conditions.

Deborah Serani, PsyD, author of “Living with Depression” and a professor at Adelphi University in New York, emphasized that although this practice is concerning, it remains legal and largely hidden from public awareness. It has been ongoing for years and represents a significant breach of privacy that places health information at risk.

The Legality Of Health Data Sales

Despite its name, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) does not provide comprehensive protection against this type of data sale.

John Gilmore clarified, “It’s a misconception to think of HIPAA as a law primarily focused on safeguarding data privacy. Data brokers are not subject to HIPAA regulations. There is no specific law governing data brokers, allowing them significant latitude in using the health information they collect and purchase.”

Gilmore further explained that HIPAA has no jurisdiction over privately shared information obtained through commercial transactions or other sources.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services specifies that HIPAA applies to health plans, healthcare clearinghouses, and healthcare providers engaged in specific electronic healthcare transactions. The law establishes national standards for safeguarding medical records and other personally identifiable health information within the scope of these entities.

Dr. Serani commented, “The deliberate sharing of patient data outside the protections offered by HIPAA is legally permissible. Our entire healthcare system relies on patients trusting that their personal mental health and medical information will remain confidential. However, this trust doesn’t necessarily extend to the digital realm, where we’ve discovered that such confidentiality may not be upheld.”

Over time, the sources contributing to an individual’s personal health profile have become more diverse and comprehensive, noted Gilmore.

“Many hospitals have agreements for sharing data and often sell data sets related to patients and medical conditions for epidemiological research. However, there are no restrictions on who can purchase this data. Thus, while it could be invaluable to those developing drugs or treatments, there are no barriers preventing consumer marketers from obtaining the same data and using it to create products,” he explained.

What are the detrimental consequences of selling health data?

The unauthorized disclosure of one’s health and mental health information to third parties can be seen as an intrusion into personal privacy. Experts warn that it can lead to several significant repercussions:

Medical Harm

When it comes to mental healthcare, individuals may be reluctant to share their challenges if they fear a breach of their privacy. This reluctance could result in some patients refraining from seeking psychotherapy or medication for their mental health issues. To alleviate such concerns, some healthcare professionals, like Serani, opt for traditional record-keeping methods such as handwritten notes, in order to maintain their patients’ privacy.

This issue could discourage people from seeking healthcare options or information from reputable sources. For instance, someone grappling with anxiety and sleeplessness who wishes to use a mobile health application for assistance might be deterred if they discover that the data they share on the app is collected and sold. They may even avoid researching information about their condition, fearing that their privacy might be compromised. This hesitance can be especially problematic as mental health issues are not always permanent, and individuals with temporary problems may choose to suffer in silence due to privacy concerns.

The sale of health data can also affect insurance premiums. To obtain insurance coverage, a medical examination conducted by a doctor is typically required, which determines the base coverage and premiums. If, during this examination, it is revealed that you are in good health, but the insurance company later discovers through third-party data that you took Prozac five years ago for depression, they might interpret it as an increased risk for depression. Consequently, you may end up paying higher premiums. This issue arises because the information used by insurance companies is sourced from commercial third parties, making judgments about individuals without transparency or control. Unfortunately, individuals lack the right to access the specific information insurers are using to assess them.

Reputational and financial harm

Because the costs of hiring employees gets higher, Gilmore said employers turn to companies that offer data analytics and consumer credit reporting to evaluate potential employees.

“[People] may not know that their red flag is based on mental health data. Employers may be scoring lower confidence in this person because they’re considering potential mental health risk,” he said.

The same is true for credit scores.

“You’d assume a credit score is based entirely on a person’s credit history, but it’s not; the people who build credit scores, they integrate every piece of information they can,” Gilmore said.

Potential Legal Consequences

The overturning of Roe vs. Wade, according to Gilmore, exposed the genuine risk of how health data could lead to legal action against individuals.

He explained that in states with restrictive abortion laws, if someone were to search for information about obtaining an abortion on platforms like Facebook, this information might be shared with law enforcement. Consequently, authorities could compile lists of individuals to investigate based on their search history.

Furthermore, individuals could face legal harm in the form of civil litigation. For instance, someone who testifies in court might find their credibility undermined if online data reveals they were taking medication for psychotic episodes. In such a situation, a lawyer could challenge the individual’s testimony by presenting evidence of their past medication use, potentially damaging their case.

Additionally, Gilmore pointed out that data collected by third parties is utilized by law enforcement for general warrant purposes. In such cases, law enforcement lacks a specific suspect and instead investigates groups of people in an attempt to identify potential suspects.

Under the Fourth Amendment, law enforcement is not authorized to pursue general warrants. However, data services have created a legal loophole that enables such actions.

For example, if there’s an incident involving a hate group, such as a racist graffiti incident with no known suspects or available camera footage, law enforcement might employ a strategy of targeting individuals in a particular area who are currently receiving mental health treatment. This approach can lead to unexpected investigations simply because someone fits a particular category or profile.

In principle, this practice contradicts the principles of the Constitution. However, as Gilmore points out, because the information collected in this manner is not used as evidence in prosecutions and is never submitted as such, it avoids being considered unconstitutional.

In Conclusion

Although the potential access and sale of your personal information may raise concerns, it’s important not to let this situation overwhelm you or lead to a heightened sense of mistrust within the healthcare sector.

As Serani points out, the majority of doctors and healthcare professionals are dedicated to upholding the confidentiality of personal information. Take proactive measures to manage what you can, and acknowledge that legal and ethical regulations are evolving in response to these challenges.

Find Us on Socials